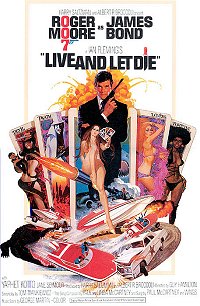

After Sean Connery turned down a dump truck full of money to return after Diamonds Are Forever, the search for a new Bond began. After their experience with a younger, less mature actor in On Her Majesty's Secret Service, producers decided on the much more experienced, and much older Roger Moore for 1973s Live and Let Die.

After Sean Connery turned down a dump truck full of money to return after Diamonds Are Forever, the search for a new Bond began. After their experience with a younger, less mature actor in On Her Majesty's Secret Service, producers decided on the much more experienced, and much older Roger Moore for 1973s Live and Let Die.

Moore's take on the role was a considerable departure from both Connery's and Lazenby's. Connery, in his early films, and Lazenby in his single outing, were brash, physical types. Moore's Bond, as befitting an older, more seasoned secret agent, tended toward caution, valuing cleverness and resourcefulness over brute strength. Though Moore's Bond fights when he has to, he prefers to cheat, and he never fights fair. The climactic fight between Bond and Tee-Hee, a killer with a mechanical arm, is a case in point. Bond and Tee-Hee battle in this train compartment, and while Bond uses improvisational weapons to good effect early, Tee-Hee's superior strength gradually gets the better of 007. When Tee-Hee has Bond pressed against the window, his mechanical claw edging close to Bond's neck, Bond notices that the wires that control the claw are exposed. He jerks to one side, grabs a pair of nail clippers, and snips the wires. He clamps Tee-Hee's claw to the metal lintel and slips free. Bond administers the coup de grace by opening the window and flipping Tee-Hee out of the train (the mechanical arm stays behind). Where Lazenby often won because he was stronger, Moore usually won because he was smarter.

The themes of Live and Let Die are tricky ones to discuss. Other commentators have wrestled with the racist overtones of both the film and its source material, particularly with respect to Bond's "rescuing" Jane Seymour's Solitaire from losing her virginity to Yaphet Kotto's Kananga. I don't have much to add to that commentary, except to note an irony: Bond's love scenes with Rosie Carver, a black secret agent, were excised when the film was shown in South Africa, owing to apartheid laws concerning depictions of interracial liaisons on stage. These scenes do vex the whole question of the film's view of miscegenation, to the extent that it becomes a white male privilege anyway. I wonder how things would have differed if screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz's suggestion of Diana Ross as Solitaire had gone anywhere with producers.

The throughline of the story is also an unusual one for Bond movies. Instead of battling a villain who has some kind of nasty technological toy, Bond's mission amounts to exposing Dr. Kananga as a heroin smuggler and drug dealer. The drug trade was already a popular subject in movies like The French Connection and Coffy, and it was certainly a temptation for the Bond people to latch onto two popular trends--drug-traffiking films and blaxploitation cinema. If following those trends makes for an interesting change from previous Bond storylines, it also dates the film far more than other Bond films from the period. The clothes, the argot, and the subject matter all scream early 1970s, which was true of neither Diamonds are Forever nor The Man With the Golden Gun (films that, though they have their own problems, seem less wedded to their era).

With all this, I make it sound as though I have nothing but complaints, and there are many things to like about Live and Let Die. The stunt work is very good, the boat chase is a knockout, McCartney's theme song is among the most memorable in the series, the atmosphere (especially in the voodoo camp and the alligator farm) is suspenseful, and the actors all do their jobs well. Special kudos to Moore though. No one thought, after Connery's final departure, that James Bond could survive into the 1970s. Roger Moore's work in Live and Let Die and his six subsequent films not only rescued the Bond franchise from oblivion but also took it to new levels of success against increasingly stiff competition from blockbusters like Jaws, Star Wars, and Raiders of the Lost Ark. Moore did something very hard to do: he took a well established character and made it truly his own.

At the age of 57, Roger Moore retired from the Bond role, handing it over to 42-year-old Timothy Dalton. His film, 1987's The Living Daylights, next time.

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Funny How the Least Little Thing Amuses Him

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment